The Great Old and Abandoned Theaters of Los Angeles

There’s nothing I can say about Los Angeles that hasn’t been said ad nauseam. So I won’t say anything. Except this one thing: it’s the best place in the world to watch a movie. I’ll dream about AMC Burbank 16 until the day I die.

If you keep an eye out, you’ll notice the city is riddled with movie theaters—operational and defunct, kitschy and classic. Some have been converted into apartment complexes or bookstores, others have been bought up by religious institutions or sit defiantly empty thanks to the National Historic Preservation Act. Of the thousands scattered across L.A., only a select few are still operating as theaters of any kind. The lucky ones. Fortunately, the architecture often stays untouched. The marquee always remains, whether utilized or not, protecting the old ticket booth if it’s still standing. The Art Deco facade may be weathered but certain ornateness can never be diminished. It doesn’t take much to be transported for a brief second to the theater’s heyday. You see the neon sign flicker to life and suddenly there’s the line of folks wrapped around the corner waiting to buy tickets. There’s a hum, an excitement, for something just inside those doors. You see how the whole street orbits in the theater’s gravitational pull.

The next moment you snap out of it. You see the same theater, dark and boarded up, now wedged between a T-Mobile store and a jewelry repair shop. But I think that magic lingers. As long as the structure stands.

I spent my last weeks in L.A. driving across the county and photographing my favorite theaters. Primarily for myself, but perhaps partly to keep some kind of record. Mine or yours, you knows. It was a fun quest, a bit like a treasure hunt, and a fitting way to say goodbye to the city.

So may I present to you: The Great Old and Abandoned Theaters of Los Angeles and what they mean to me.

The Rialto, located in South Pasadena, was built in 1925 by architect Lewis A. Smith who constructed several others theaters across L.A. (most notably the Vista mentioned below). According to this epic Los Angeles Theatres blog, the opening night showing was the silent film What Happened to Jones. For the steep price of 30 cents you could also catch up-and-coming vaudeville acts preform before the show. The theater seemed to operate steadily until the ‘70s when ownership changed hands and it was registered with the National Registry of Historic Places. It ceased operations entirely in 2007, ushered out by its final showing: The Simpsons Movie. For the next decade, it sat empty and unowned until 2017 when a Christian mega-church, Mosaic, moved in—at the very least saving the theater from demolition.

You might recognize this theater from my favorite film ever made, La La Land. It’s where Seb takes Mia to watch Rebel Without a Cause on their first date. When I visited L.A. in 2017 to tour colleges, I forced my mom to drive us all the way out to Pasadena so I could see the famed theater for myself. My heart broke a little to find it no longer screened movies.

As the Rialto was my first beloved L.A. theater, it felt like the right place to begin.

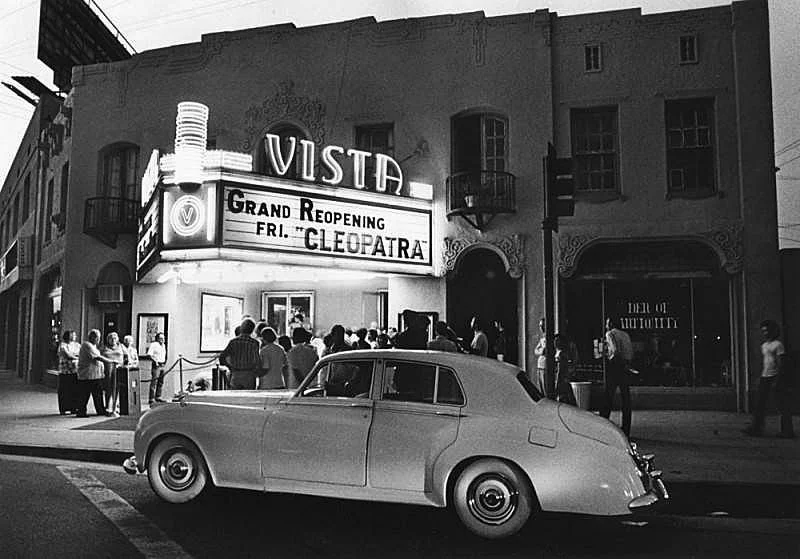

Vista Theater, 1980. From the Los Angeles Public Library.

Another one of Lewis A. Smith’s designs, the Vista, sits right at the junction of Sunset Blvd. and Hollywood Blvd. (which is an insane six-way intersection) in East Hollywood. It originally opened in 1923 as “Bard’s Hollywood,” named after its owner Louis L. Bard, who was the mastermind behind many of the city’s earliest theaters. Similar to the Rialto, the interior of the Vista is “Egyptian flavored,” which seemed to be all the rage back then. The first film screened here was Tips, a short silent film starring a child named Baby Peggy. Bard sold the theater in 1927, when it was officially renamed the “Vista” and endured several decades of programmatical flux—first it showed foreign films, then pornos; it briefly became the epicenter of (non-pornographic) gay films in the 80s, and eventually began showing revival films. The theater felt like an immovable part of the East Hollywood/Los Feliz community until 2020, when the pandemic shuttered its doors. But a year later, director Quentin Tarantino swept in to save the Vista (he already owned the New Beverly mentioned below). Finally, on its 100th anniversary in 2023, the Vista reopened to a mad crowd. The program is currently a mix of new releases and old movies, either part of Tarantino’s own collection or on loan from the nearby studios. The best part? Everything screened is on actual film—16mm, 35mm, or 70mm. It was Tarantino’s one request.

The Vista is my favorite theater in the entire city. It has the comfiest seats, best concessions, greatest audio and visual quality. It’s so dark and cold in that theater and always packed full of people. I first discovered the Vista because I was looking for places that screened old movies. Nothing comes closer to time travel than watching an old movie on the big screen. The Vista was showing The Philadelphia Story at 10 A.M. on a Sunday morning, so I bought myself a ticket and rolled up in my pajamas. Up to that point, I’d found that L.A. wasn’t the kind of place people got up early on the weekends. I figured the theater would be empty and I was safe in my pajamas. I was not safe in my pajamas.

The 10 A.M. showing of The Philadelphia Story was sold out. The place buzzed with both children and the elderly, popcorn-for-breakfast eaters, groups of friends and solo watchers alike. Once I recovered from the surprise, I was filled with an absurd love for humankind. I never liked L.A. more than in that very moment. Weekend matinees at the Vista became my little tradition.

Studio City Theatre, 1938. From the Los Angeles Public Library.

The next stop on this theater tour is Studio City, the best neighborhood in L.A. if I say so myself. The Studio City Theatre opened in 1938, with the Clark Gable film Test Pilot, taking up prime real estate on Ventura Blvd. Though a beautiful, grand building, the theater changed hands quickly and tumultuously for decades which never allowed it to flourish. While most single-screen cinemas were converted into multiplexes in the 80s and 90s, the Studio City Theatre was deemed too small to do so and ceased operations in 1991. Ironically, one dying industry saved another. An early subsidiary of Barnes & Noble, BookStar, moved in before officially becoming its parent company in the early 2000s. The interior and exterior remain movingly untouched and, when you step inside that Barnes & Noble today, you can imagine exactly how the theater used to look. The ticket booth stills proudly stands guard out front.

Like how the Vista became my local theater, this became my local bookstore. These few blocks of Ventura Blvd., truthfully, feel like the site of my L.A. life. Across the street is the Studio City Farmer’s Market that I frequented with my best friend Alyssa. Around the corner is the neighborhood where I saw Jeremy Allen White once. And down the street from there is my beloved Peet’s Coffee where I spent hours working and hiding from my crazy roommate. What more could a girl need?

When I think about the converted Studio City Theatre, I feel a bit like Meg Ryan at the end of You’ve Got Mail. Yes, her perfect little family-run bookstore closed and was bought out by a soulless corporation (literally Barnes & Noble). BUT she learns there actually is soul in that corporation and things aren’t so bad. I have a sneaking suspicion the bookstore version of this theater is doing better than the theater version of this theater ever did…

The Million Dollar Theatre is the oldest on this list, opening in 1918 with the premiere of a silent Western The Silent Man. This marked famed entrepreneur Sid Grauman’s first Los Angeles-based venture. He and his father made a name for themselves by opening some of the first theaters ever in Northern California, first for vaudeville performances and then silent films when they gained popularity in the early 1910s. They traveled down south to place their chips on the budding metropolis of Los Angeles like everyone else. With money to burn and ambition unchecked, Sid Grauman began construction on the first movie palace in Downtown Los Angeles. Because of him, the main thoroughfare downtown, Broadway, would soon house the highest concentration of movie palaces in the country. The Million Dollar Theatre, though officially named “Grauman’s,” earned its colloquial title due to its actual price tag. A running gag of sorts. Rumor has it, the ornate sculpture work above the marquee was “one of the costliest theater entrances ever built.”

For a few electric years Downtown L.A.’s Broadway was like a movie set of its own. Every famous actor and director lived nearby, walking to extravagant premieres and theater openings every weekend. Major industry hadn’t arrived yet—all there was to do was make movies and watch movies. If you needed Charlie Chaplain, he was probably hanging out with Grauman in the back office of the Million Dollar Theatre. In 1923, Grauman set his sights elsewhere: Hollywood. He sold the Million Dollar off and went on to build the Egyptian and Chinese Theatres, both on Hollywood Blvd., that still operate today. When the movie business left Downtown Los Angeles, so did the glitz and glam. Nonetheless, the Million Dollar had a long run as a Spanish language theater until it closed in 1993. It was briefly leased out to a few churches, but has sat largely empty since 2012.

I stumbled upon the Million Dollar Theatre when my friend Emma and I explored downtown last summer. We rode Lime scooters recklessly down the streets, ate lunch at Grand Central Market, perused the Last Bookstore, and stared at all the grand, old buildings that aren’t so grand anymore. It’s not hard to find downtown, specifically Broadway, unspeakably depressing. Coming across this epic artifact of a bygone era and seeing the words “Life is hard. Tacos help.” displayed on the battered marquee made me want to collapse onto my knees, shriek, and pull out my hair like a mad woman. I wanted to curse the Industrial Revolution and man’s greed. Alas, I refrained.

Though it’s harder, it is not impossible to also find inspiration downtown. Because the streets continue to buzz with life, just not in the Golden Age of Hollywood way. These historic buildings are still standing, after all, having adapting to this modern era or simply waiting for their chance to.

Fairfax Theatre, c. 1930. From the LA Conservancy.

In the spring of 1930, the Fairfax Theatre opened at the cross-section of Fairfax Ave. and Beverly Blvd. What is now the main drag from the westside to the eastside was then just a small Jewish neighborhood. This theater became the “first major commercial building in the district.” It premiered the film Trooper’s Three on its opening night and quickly cemented itself as a local haunt. Symphony concerts, vaudeville acts, religious events, and benefit galas all occurred within its walls. It seemed to have a good, long life before shuttering in 2010 after torrential rains damaged the roof. The owners wanted to make money fast, instead of preserving the space, and tried to get project approval to build an apartment complex on top of it. Apparently the city would only agree if they kept the facade untouched. That is how the theater remains now—a husk of a building—in a years-long stalemate between government preservationists and the money-hungry owner.

My parents would be ashamed to learn I took this photo out of my car window while stopped at a red light. I found the Fairfax by accident, by merely glancing out my window and recognizing that Art Deco flare. And the marquee. The marquee’s a dead giveaway. But then I drove away and forgot entirely where it was, except somewhere along Beverly. My only solution, when it came time to photograph these theaters, was to drive up and down the boulevard until I found it. Forty-five minutes later, there it was to my left at a red light. Totally worth it.

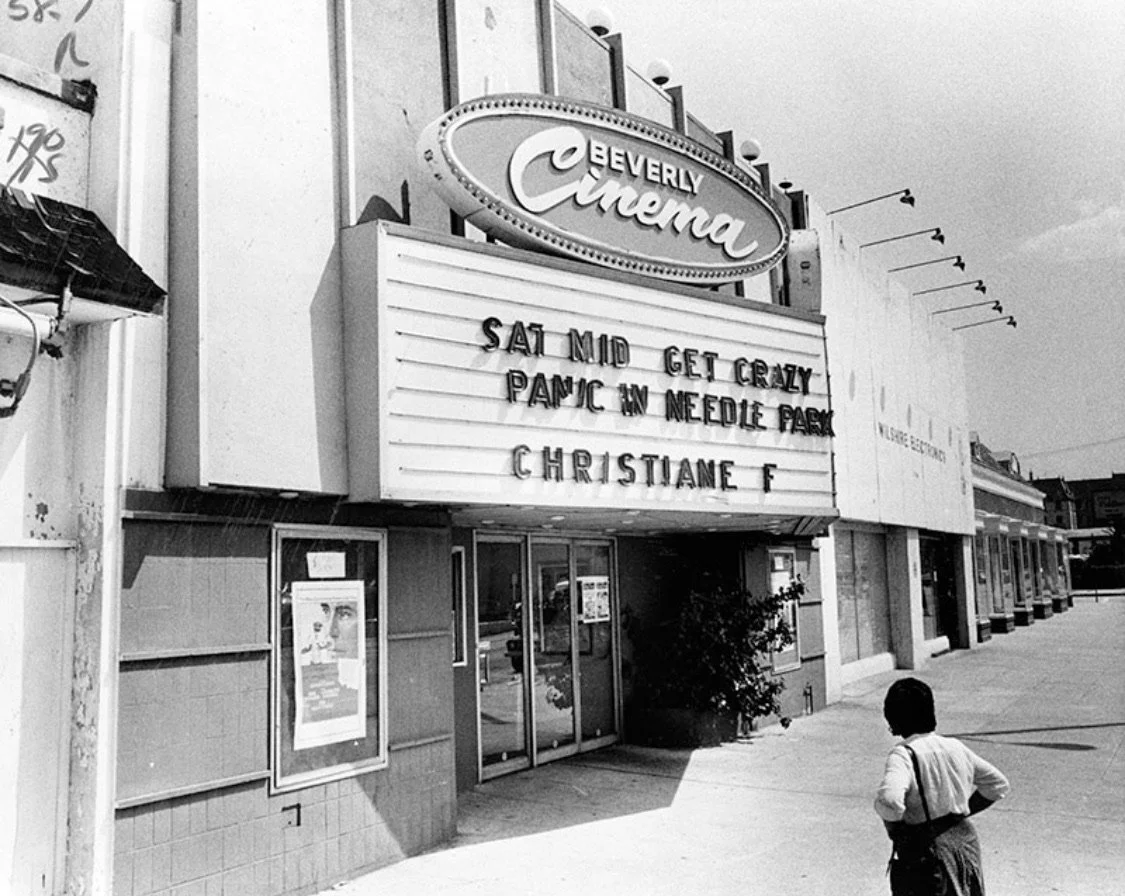

New Beverly Cinema, 1983. From the Los Angeles Public Library.

Also off Beverly Blvd. is, of course, the New Beverly Cinema. When constructed in 1929, the building had no intention of being a theater. It was a candy shop, then an ice cream parlor, then a winery, then a nightclub featuring a boxing ring. Not until 1949 did it become a theater, though only for stage plays. The theater as it stands today opened in 1972 as the “Beverly Cinema” with the erotic film The Young Starlets. It’s porno chapter was short-lived and, under new owners, became a revival theater highlighting double features. The owner, Sherman Torgan, died tragically in 2007 and the locals thought the Beverly was surely done for. Until Quentin Tarantino decided to make his first foray into the theater-owning business. Renaming it the “New Beverly,” the theater continued its regularly scheduled programming under Tarantino’s promise: “As long as I'm alive, and as long as I'm rich, the New Beverly will be there, showing double features in 35mm.” Aside from a brief stutter during the pandemic, this theater is alive and well.

Something beautiful happened to me at the New Beverly. I bought myself one ticket to watch the Katharine Hepburn double feature of The Philadelphia Story (I am nothing if not loyal to the films I love) and Sylvia Scarlett on a random Tuesday night, when I show up and find one of my nearest and dearest friends, Abby, waiting outside. What was she doing there! She lived across town! Only movie magic could orchestrate such a twist of fate. My solo adventure turned into a hilarious hang-out because Abby and I quickly learned that Sylvia Scarlett is one of the worst movies ever made. The script felt like something written by a child filling out Mad Libs and it’s painfully obvious that Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant hadn’t yet nailed down their dynamic.

Los Angeles Theatre, 1931. From the California State Library.

Our last stop on this tour is back in Downtown L.A. at the astutely named Los Angeles Theatre. It opened in 1931 with the premiere of Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights, where allegedly Albert Einstein was in attendance. The builder initially imagined this theater to be “the largest theater west of Chicago.” Though that dream never actualized, the Los Angeles did turn out to be one of the most magnificent structures on Broadway, modeled in the French Renaissance style unlike many other movie palaces that were Spanish or Egyptian inspired. It became the last epic palace built on the thoroughfare—the industry had almost entirely moved to Hollywood by this time. It came as no surprise that the theater ran out of money months after opening and was sold off to Fox West Coast, the mega-theater chain that owned every historic theater in L.A. at one point or another. Nonetheless, the Los Angeles continued showing current films until 1994 when it ceased operations. The building is now owned by one incredibly wealthy family with supposed plans to revamp the theater, yet it has sat empty for over thirty years. Occasionally it is used for filming and shots of the interior can be seen in Gattaca, Armageddon, The Prestige, and Fight Club.

We end here for no other reason than because it’s the photograph I’m most proud of. The comparison between the opening night photo and this one is stark and painful. Everything is just as it was—from the painted ad on the building to the left, to the futilely ornate facade—but nothing is the same. As I walked down Broadway on one of my last days in L.A., the Los Angeles Theatre struck me like a gut punch. Something about the T-Mobile store particularly irked me. I guess you could say I was having a hard time digesting the passage of time, but that seems to be happening to me a lot these days.

I don’t know what I want from these old and abandoned theaters, specifically the ones that remain empty. I don’t think I want anything at all. Just to be reminded of them, even if it hurts, is enough.